Like the rest of Ireland, Dublin has a lot of history, and not much of it is happy. Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin’s former prison, is no exception; many leaders and revolutionaries were imprisoned and executed there. It’s one of the most interesting historical sites in Ireland, and one of the most visually appealing. Several films have featured it, including The Italian Job from 1969.

When I got to Dublin, I hadn’t planned on going, but a couple of girls I met in the hostel (one from Austria and one from France) highly recommended the Kilmainham Gaol tour to me over breakfast. They told me I’d have to make a reservation but that it was worth it. So, since I had a few free hours left on my last day there, I decided to give it a try.

It was a long walk out to the jail from Dublin center. It took me about twenty minutes, but that could be more or less depending on the part of the city you’re coming from. It was a fairly pleasant walk. The Gaol was easy to find, and on the way back I stopped at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and St. Adouen’s church.

A bit of background on the Gaol

The New Gaol opened in 1796, replacing an older prison system. Kilmainham Gaol was part of the prison reform movement, and shifted away from the disorder and unhealthy conditions of earlier prisons. Inmates were kept separate from each other, the jail was built on a hill for better drainage and air circulation, and rules (on food, conduct of guards, etc.) were set and enforced to reduce violence and increase prisoner health. Unfortunately, the jail soon became overcrowded and ended up with many of the same problems as before, in spite of the intended reforms.

At first, the Gaol was kind of a transition place for prisoners who would eventually be sent to Australia. According to the tour guide, during the first fifty years or so that the jail was in operation, over four thousand people were transported to Australia. Later on, many of the inmates were political prisoners, held by the British. They were rebels or revolutionaries of the many rebellions from 1798 to the civil war in 1922-23.

Like I said, overcrowding was an issue. With all the political prisoners, prisoners awaiting transportation to Australia, and ordinary criminals (arrested for things as small as stealing food), plus the incarceration of those with mental illnesses, they were forced to put multiple people in cells designed for one person. Things got even worse when they started arresting beggars, and worse still during the famine years. People were desperate for food, and they knew that there was, at least, food in the jails, so many of them decided they’d be better off being arrested than living in the horrible conditions at home. The food in the jail was miserable (bread, corn meal and milk), but it was preferable to starvation.

“If the prison does not underbid the slum in human misery, the slum will empty and the prison will fill.” – George Bernard Shaw

I thought that quote, which was displayed in the small museum at the end of the tour, was quite relevant.

Of course, if you have enough money, the rules don’t apply to you. I recently re-read Around the World in Eighty Days, and I have to say, the thing that stood out to me most this time was the amount of money they spent and what it actually got them. I mean, at one point they missed their boat, so they bought out the captain and bought a new boat and then burned the upper part of it as fuel when they ran out partway across the ocean. It’s insane, but it worked. When my friend and I missed our train from Mont Saint-Michel, I remember wishing we’d had enough money to buy our way out of the situation. We could have bought a train, or a car, or even a bus!

Money worked for high-profile prisoners at Kilmainham like Charles Stewart Parnell, too. He was a political prisoner, but unlike the others who were stuck in those small, crowded cells eating horrible food, he bribed the guards and got two enormous cells to himself, had his own furniture brought in, and got the right to interact freely with any visitors who came for him. He even got to leave the prison once or twice during his sentence.

Joseph and Grace

One of the most touching stories from the Gaol’s glory days is that of Joseph Plunkett and Grace Gifford. Joseph was a young, wealthy Irish nationalist and leader of the 1916 Easter Rebellion against the British. Grace was an artist and a caricaturist, and active in the Republican movement. Grace was introduced to Joseph in Dublin by a friend and journalist who Grace had met through her artistic work for the local newspapers. The two hit it off, and Joseph proposed about a year later. They planned to be married on Easter morning, 1916.

Of course, that was the same day the Easter Rising would happen, and Joseph, as one of the leaders of the rebellion, was part of it. Already suffering from poor health, he was arrested during the uprising and sentenced to execution. He was held in Kilmainham Gaol. Grace found out that he would be killed, and decided she wanted to marry him before it was too late. She bought a ring at a jeweler’s shop, and got a priest to help her convince the authorities to let her see her fiancé just hours before his execution. She and Joseph were married in the chapel in Kilmainham Gaol, they got a few moments to say their goodbyes, and then he was taken outside to the courtyard and executed, as were so many others before and after him. Grace never married again.

Here’s a pretty Irish ballad about their relationship. It was written in the 80s and has been recorded and covered by plenty of groups since then. It’s called “Grace.” This one is one of the most popular versions on YouTube:

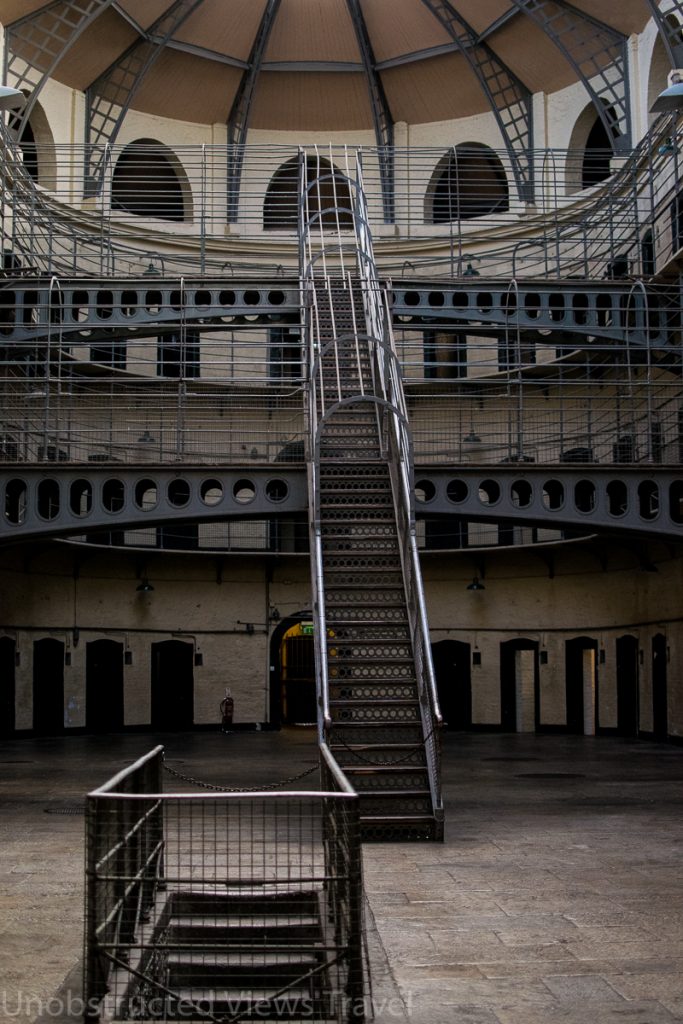

The east wing

This is the part of the gaol that is most famous, because it’s been used in the filming of so many movies. It’s an enormous, open room shaped like a horseshoe. The idea was to allow the guards to see all of the rooms at once, improving security. Grace Gifford’s cell was one of those on the bottom level in this room.

The skylight also plays an important role. It was placed deliberately to encourage prisoners to look up, to the source of the light. The architects hoped that this would lead the prisoners to think of God and seek forgiveness for their mistakes. The small, high windows in the cells were designed according to this same philosophy.

Some of the most interesting things I learned:

I don’t want to give everything away, but here are some of my favorite things from the tour.

- The serpents carved above the entrance represent evil restrained by justice.

- The Irish flag: green represents republicanism, orange represents loyalty to the British, and white represents hope for peace

- When prisoners were taken out to be shot (always one at a time), they were shot by a firing squad of 12 people. Eleven of them had real bullets in their guns and one person had a blank. That way, no one would know who delivered the killing shot.

- One of the biggest causes of the famine was a mysterious disease that affected the potato crops. When they dug up the potatoes, they looked fine, but within days they shriveled, rotted and became inedible. Now we know that it was an airborne fungus, but the Irish back then didn’t understand what was happening, or how to fix it.

- The jail fell to ruin in the 1940s and was almost destroyed, until a group of ex-prisoners petitioned and started a grassroots movement to restore the building. It’s a good thing they did!

- In a poll of museum visitors on the death penalty (for or against), the results were nearly half and half, but the “against the death penalty” group had a slight edge.

Also, did I mention I got in for free? This was the day after my wallet got stolen. I wasn’t able to book online because I didn’t have a credit card, so I just went early to the jail hoping to get a spot in a later session. When I asked the employee for one of the discounted student tickets, I explained that I didn’t have any proof of age because my driver’s license and international student cards had been in my stolen wallet. I think she felt bad for me, because she asked the ticket seller to give me a free entry and to let me on the next tour even though it was full. It was very nice of her, and I did get my ID cards back a couple of weeks later when the rest of my wallet was found and mailed to me.

Practical Information

For everyone else who wants to visit and is not a solo female traveler without identification, the rates for a 90 minute tour are still pretty cheap. Adults: 8 euros. Seniors: 6. Students and children: 4. Family rate: 16. If you book online in advance, you get to take an extra euro off of that price, and you’ll be sure to get a spot on a tour. It’s a popular attraction, so the tours (which have a cap of 35 people) fill up fast. You can find all the practical information on their website, including the recommendation to bring a jacket because it gets pretty cold in there.